Today is the first day of fall, so it seemed like a particularly appropriate time for an autumnal recipe – Jennie Martin’s Brown Betty. Regular Around The D Readers might remember Jennie Martin from a previous Recipes from the Archives blog post – her Cafe Parfait was featured this summer.

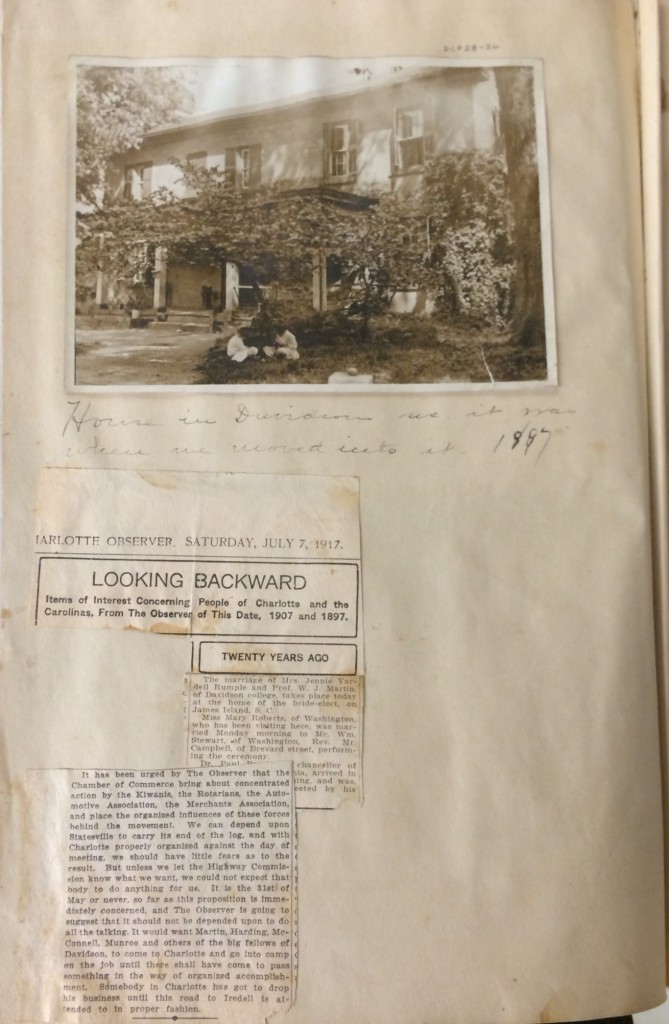

Jane “Jennie” Vardell Rumple Martin (1872 – 1955) hailed from Charleston, South Carolina, and first came to North Carolina to attend the Charlotte Female Institute (now Queens University). Jennie moved to Davidson in 1897, when she married William Joseph Martin, Jr. (1868 – 1943; Class of 1888), then a professor of chemistry at Davidson College. W.J. Martin, Jr. was the son of Colonel William Joseph Martin, a Davidson College professor of chemistry and geology who served as acting College President from 1887 to 1888. W.J. Martin, Jr. became President of the College in 1912, a post he held until 1929, when he was appointed President of the Assembly’s Training School (now Union Presbyterian Seminary) in Richmond. The Martins returned to Davidson in 1939 and remained in town for the remainder of their lives. The family included five children: J. Malcomson Rumple (Jennie’s son from her first marriage to James Rumple), William Joseph Martin III, Eloise Martin Currie, Jean Martin Foil, and Mary Martin Maddox.

As noted in the previous recipe entry on the Martins, Jennie was very active in town life – she founded the Woman’s Book Club of Davidson (now Booklover’s Club) and the Young Matrons Club (Twentieth Century Club from 1927 to 1964). She contributed recipes for the Davidson Civic Club’s Davidson Cook Book (circa 1928).

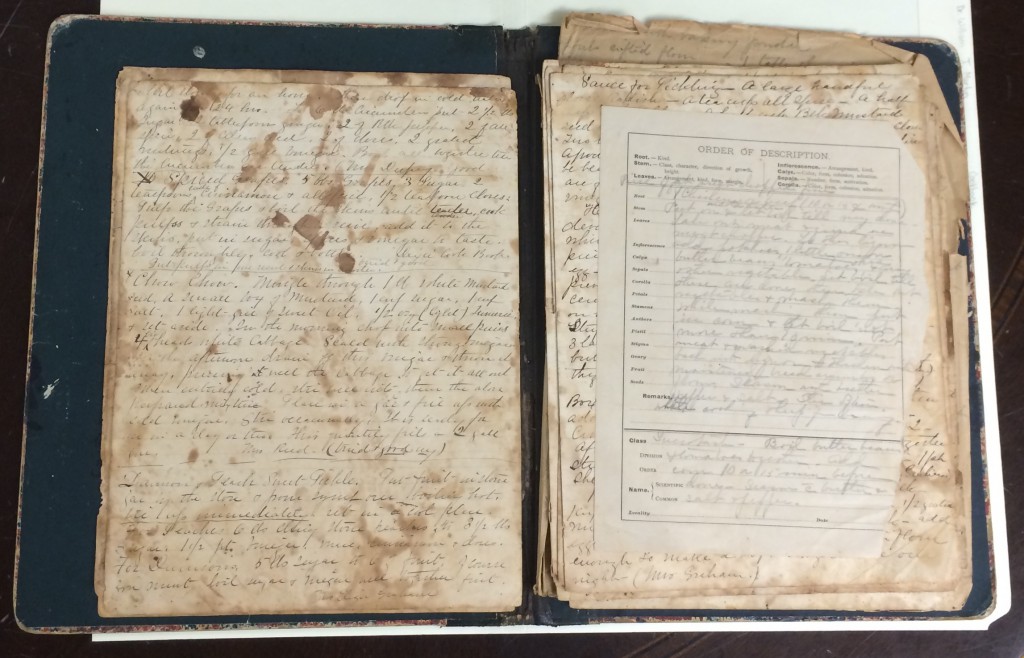

Jennie Martin’s cookbook was likely compiled sometime between 1897 and 1907, based on dates from a scrapbook also created by Martin during her time in Davidson. Most of the cookbooks in the Davidson College Archives & Special Collections are collections of recipes gathered from several community members and published as a fundraising activity for various civic or social organizations, but the Martin cookbook is a handwritten, personal collection of recipes.

Likely the recipes Jennie Martin recorded in her cookbook were shared from her family, friends, and neighbors – as Janet Theophano states in Eat My Words: Reading Women’s Lives through the Cookbooks They Wrote, “From at least the seventeenth century, women have exchanged and shared recipes (also called receipts until the late nineteenth century) that they recorded in their cookery manuscripts”; these recipes “may come from past generations and from individuals living side by side in small communities, connected to larger social circles, sometimes from one or more cultures, and they can also come to the cookbook from an array of print media.” (pages 8-12) Recipe books compiled for personal use also often contain notes on how the recipe turned out, whether an ingredient was substituted, or if the recipe needed to be modified in any other way.

I chose the recipe for Brown Betty from Martin’s cookbook partially because the recipe is seasonally appropriate, and partially because I had heard of but never made the classic dessert before. The Oxford Companion to Food (3 ed.) lists a “brown Betty” as a North American “baked pudding” that first appeared in print in the Yale Literary Magazine of March 1864. The origin of the name remains unknown, although given the capitalization of “Betty” since the first published reference, many have concluded that it refers to a person.

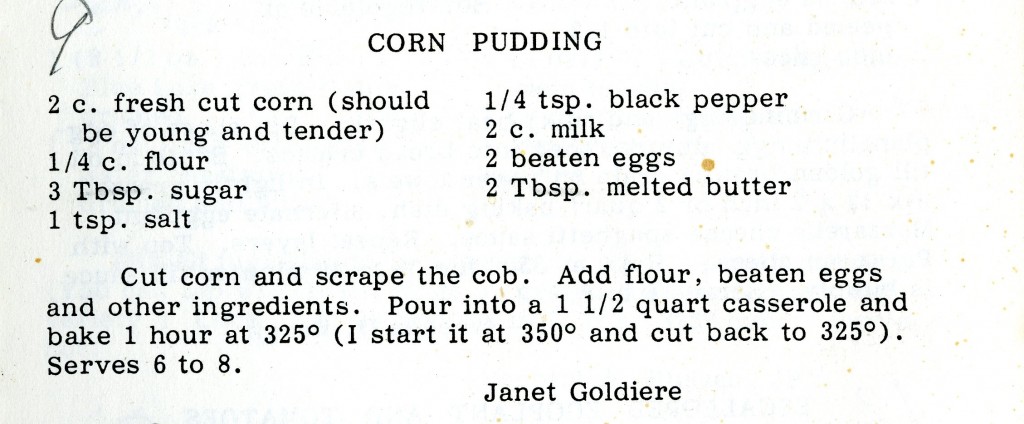

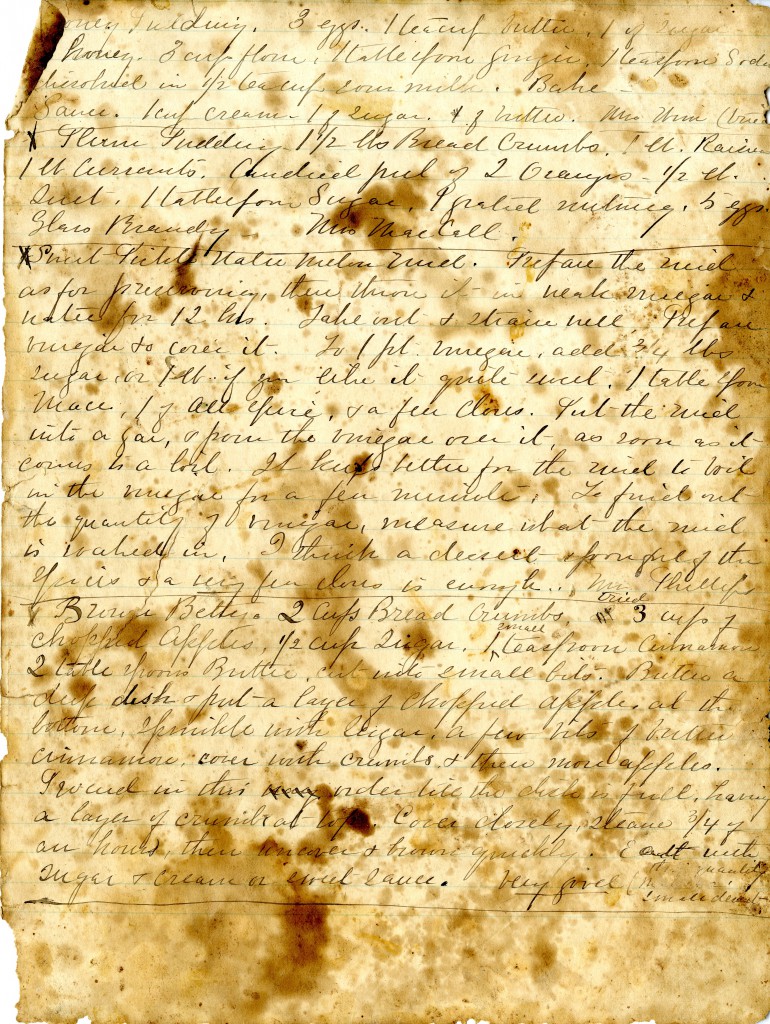

Martin’s recipe calls for: “2 cups bread crumbs, 3 cups chopped apples, 1/2 cup sugar, 1 small teaspoon cinnamon, 2 table spoons butter, cut into small bits.” I made breadcrumbs out of half a loaf of Italian bread – dried out in the oven to remove moisture, cut into small pieces, and then chopped finely in a blender. Since the type of apple isn’t specified and the modern versions of the recipe diverge greatly on apple variety, I chose Cripps Pink Lady apples (swayed by this Bon Appétit piece on the best apples for baking). I followed Martin’s instructions for layering the apples, sugar, and breadcrumbs, with dashes of the cinnamon and the “small bits” of butter thrown in.

Interestingly, the recipe apple Brown Betty has remained mostly unchanged – Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald’s America’s Founding Food: The Story of New England Cooking notes that “One early-twentieth-century Brown Betty recipe called for ‘one loaf of stale bread crumbled fine, one-half cupful of milk, and twelve apples. Alternate layers of bread and sliced apples, sugared, buttered, and spiced. Moisten with milk. Bake in a tin pudding-pan for three hours.'” (page 206) Note how similar the ingredients and instructions are to both Jennie Martin’s recipe, and to present-day versions.

Stavely and Fitzgerald also note the popularity of using apples in creating various beverages and dishes in colonial America – the fruit flourished in New England beginning in 1625. Using stale bread and apples possibly gathered from a nearby tree, Brown Betty could be an easy and affordable recipe to make.

Many of the recipes I’ve encountered in our archives do not list oven temperature or baking time (and in any case, the bake time in a modern oven may vary from the historic recipe), and although Martin’s Brown Betty does not specify a temperature, she does note that to bake the dish, you should “cover closely, steam 3/4 of an hour, then uncover + brown quickly.” I took a note from modern versions of the recipe and cooked the Brown Betty with tin foil covering the pan for 45 minutes at 350°, then removed the foil and cooked for an additional 15 minutes.

As Martin notes at the close of her recipe, this Brown Betty is best to “Eat with sugar + cream or sweet sauce. Very good.” All in all, an easy and delicious historic dish!