In honor of Black History Month, this week’s blog focuses on the experience of first black students at Davidson College, from Benoit Nzengu’s admission in 1962 to the graduation of Denise Fanuiel in 1977, particularly through their own words and reflections. Last week’s post provided some background on the policies and attitudes surrounding integration at Davidson, from the mid-1950s until Fall 1962. For a broader view of black history in Davidson, check out the short documentary Always Part of the Fabric and its accompanying text supplement.

In Fall 1962, Benoit (Ben) Nzengu enrolled at Davidson College. Nzengu, the son of a Presbyterian minister, was educated in Kasha and Lubondai (Democratic Republic of Congo). Two of his teachers in medical programs were missionaries who had attended Davidson – Dr. William Rule (Class of 1932) and Dr. Hugh Farrior (Class of 1949). He moved to Kingsville, Texas in 1961 in order to attend the Presbyterian Pan American School and apply to colleges in the United States. Ben then spent the summer of 1962 studying at the Institute of Modern Languages in Washington, DC and taking a course at Howard University before being put forward for admission to Davidson by the Presbyterian Board of World Missions. Originally given the standing of “special student” (i.e., a student not in a regular four-year degree program), the Admissions Committee evaluated his record in May 1963 and determined that Nzengu should be admitted as a freshman for the following year. However, he graduated on time in 1966 due to taking summer courses, and went on to study medicine at the University of Brussels. Dr. Nzengu is now a surgeon in France.

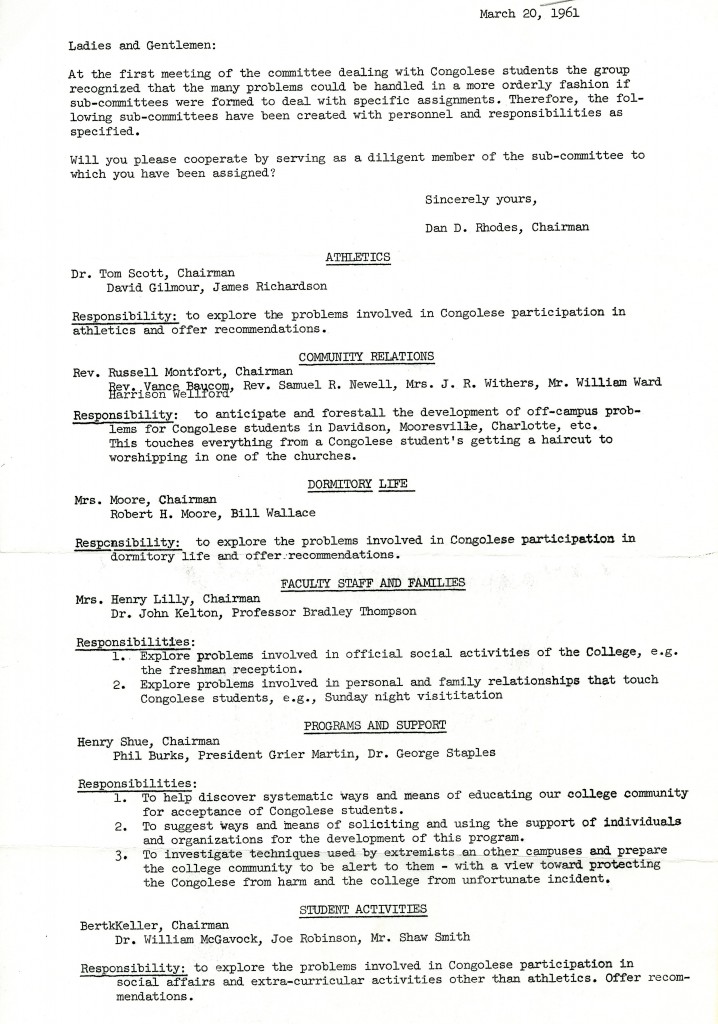

Professor Dan Rhodes (Class of 1938, religion professor 1960-1984), who chaired the committee tasked with “dealing with Congolese students,” served as Nzengu’s faculty advisor. Special consideration was given to who should room with Nzengu; it was decided that Knox Abernethy (Class of 1963) was good choice, as the Board of World Missions advised against placing Nzengu in a room with a missionary’s son who had spent time in the Congo:

“We find it hard for the missionaries not to be too paternalistic. We feel that it is good that Benoit will be accepted for what his is now, rather than what may be known about him in the past in terms of his life and growth in the Congo; we think Benoit has what it takes to make the grade. We find that it is awfully hard for the Congo missionaries and their families not to always be thinking about our Congolese friends as they used to be rather than as they now are.” (Letter from George M. Cooley to Dan Rhodes, August 6, 1962)

In September 1962, then College President D. Grier Martin communicated with Charlotte movie theater owner Mike Kincey about whether Nzengu would be allowed to attend showings of films at one of the three theaters owned by his company. Martin’s letter spells out how difficult dealing with segregation in Charlotte and its surrounding areas must have been for Nzengu:

“It occurred to me that an exception might be made at one or more theaters if this boy were accompanied by at least two of our Davidson students who would agree to sit on either side of him so that no person who might object to sitting by a colored person would have this happen.”

Martin’s letter to Professor Dan Rhodes on September 17, 1962 about the protocol for Nzengu’s attending movies starkly demonstrates the lengths Nzengu had to go through to avoid humiliation or violence while participating in activities that his fellow Davidson students could do with ease.

Being able to participate in leisure activities like other Davidson students did remained an issue – as Rhodes commented May 8, 1981 Davidsonian article by Minor Sinclair and Vince Parker: “‘It took us some time for real non-segregation to penetrate all fibers of the College and community. It’s the little things – like being able to get a cup of coffee, or to use a public restroom, or get a haircut – that makes a difference and that are so hard to grow into,’ [Religion Professor Dan] Rhodes added.”

Archival records indicate that Ben Nzengu was in regular contact with the Board of World Missions, and that he was also under a microscope in many ways. Newsweek sent a reporter to cover his experience at Davidson, The Charlotte News ran a story on his adjustment to college, and the Davidson College Public Relations office took several publicity photos.

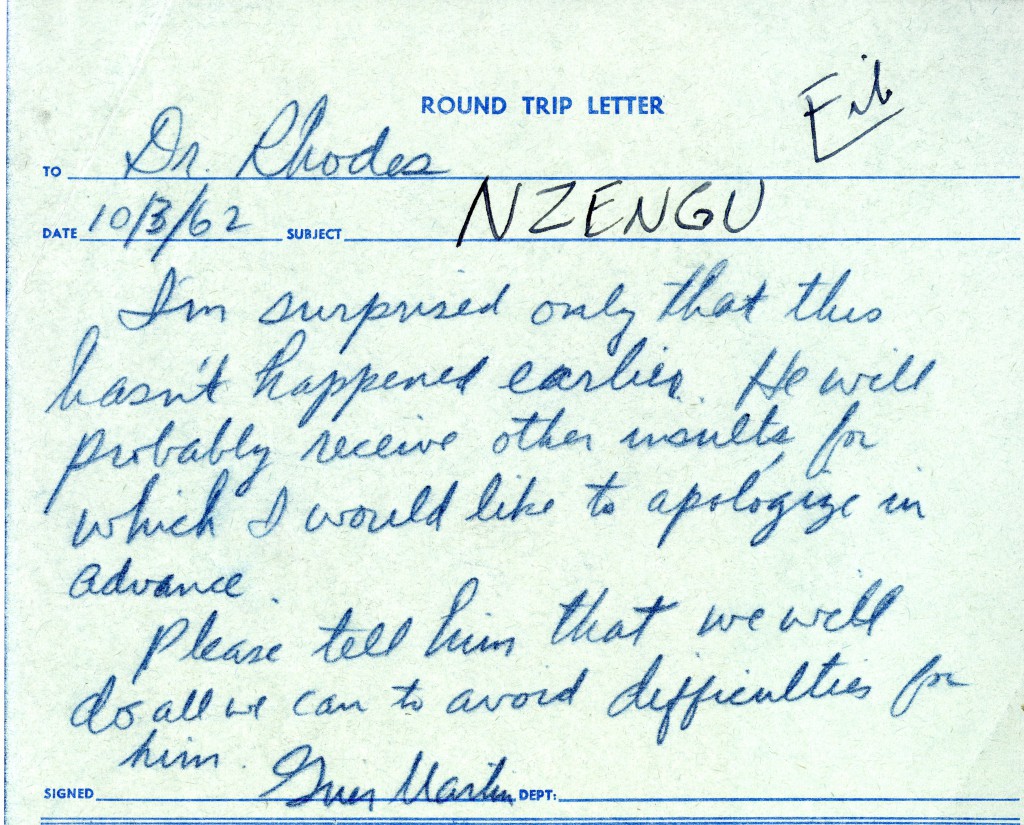

The same week that The Charlotte News reported that “Ben hopes to study hard and make lots of new friends,” Nzengu received some hate mail. President Martin’s response to Dan Rhodes, who had reported the incident, notes that the College President was “surprised only that this hasn’t happened earlier.” President Martin was also receiving hate mail during this time period, primarily from alumni who found integration repugnant.

In April 1963, the United States Information Agency’s H.S. Hudson wrote Robert J. Sailstead (then Davidson’s Director of Public Relations) on the subject of doing “a brief picture story on Mr. Nzengu” for the July issue of Perspectives Americaine and American Outlook, published by the Information Agency in Leopoldville and Accra, respectively:

“In general, we want coverage demonstrating Nzengu is accepted by his fellow students, participates in college life, and demonstrates that he is satisfied with being in Davidson. If he is also accepted by the townspeople, then shots to this effect would be very useful.”

In Fall 1963, Nzengu was joined by the second black student to enroll at Davidson college – Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, also from the Congo. After graduating from Davidson, Nzongola went on to get a master’s degree in Diplomacy and International Commerce from the University of Kentucky in 1968, and a Ph.D in Political Science from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1975. Dr. Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja is currently a professor of African and Afro-American studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He served as a visiting professor at Davidson for the Fall 1990 semester. While a student at Davidson, Nzongola, led “a fight for liberalizing church attendance policy”:

“At the time, all students were required to attend chapel two or three times a week, Sunday evening vespers, and Sunday morning church services – for which they had to have signed attendance slips. But students had only three choices for church attendance – the college Presbyterian church, the Methodist church, and the Episcopal church – all white middle class churches. There were two other churches in town, the black church and the poor white church, but neither of them counted towards the attendance requirement. ‘You couldn’t even go to the poor white Presbyterian church and get an attendance card,’ Nzongola recalls. ‘So I said, ‘I’m going to go to the black church, and you have to give me an attendance or not give me an attendance.’ So finally they relented, and eventually every student was able to get attendance in any church they wanted to attend.'” (“The Black Experience of Davidson” issue of the Davidson Journal, Fall 1990)

Both Nzengu and Nzongola were on the soccer team, and Nzengu earned All-Southern Conference honors as a varsity soccer player.

In Fall 1964, the first black American students enrolled at Davidson, Leslie Brown ’69 and Wayne Crumwell ’68. Brown’s son, Demian Brown Dellinger (Class of 1998) was Davidson’s first black legacy student. The May 1, 1964 issue of The Davidsonian announced: “Two American Negroes Plan to Enroll This Fall: Three Boys Admitted, But Only Two Accept.” Former Student Body President, John Spratt (Class of 1964) was quoted as saying:

“This will be a terrific challenge for Davidson boys who profess beliefs in integration to act out their convictions. I hope there will not be a de facto segregation within the student body against these young men and that they will become full members of the student body in every sense of the word: intellectually, politically, and socially.”

During Homecoming 2012, the Offices of Multicultural Affairs and Alumni Relations sponsored a program called “Reflections: On 50+ Years of Integration,” featuring keynotes by Ben Nzengu ’66 and Leslie Brown ’69. The Davidsonian article covering the event noted: “Today, 24.2% of first-year students identify as students of color. Fifty years ago, there was only one student of color.” Nzengu reflected at the event: “How great a role did Davidson play in my life? To give you an idea, it was Davidson and its Board of Trustees who made it all happen in 1962, the year I was admitted here to integrate a southern white male college, in a year in which only 53% of the student body was in favor of having black students among them.”

Nzengu went on to talk about how his friendship with James Howard, a college employee, gave him insight into the life of black workers at the college and black life in town:

“…[Howard] was in charge of the Chemistry Building, and a very skilled worker. He was paid as a janitor. I know him well, and I used to go eat at his house, and go with him to his Church, across the railroad tracks. Life on the other side of the railroad tracks was a distinctive mark for the entire black community. One day, I had the following conversation with James. ‘The whites in this town would like us to stay in the same position working for them and doing the dirty work with low wages,’ he said. ‘The separation between our two communities is these railroad tracks; you cross it to go to work, you cross it again to go back to your house, and that’s it.’ ‘Before you came to Davidson,’ he added, ‘everyone in town knew that a Congolese student would be coming to Davidson, but the whites don’t like to see integration, and black people crossing those tracks permanently.'”

At that same event, Brown said of his experience:

“Coming to Davidson as one of the first black students in the time of rapidly emerging and advancing civil rights movement, I saw myself as having assumed the mantel of ‘firstness.’ By that I mean, I had embarked on the migration with a sense of mission, duty, and responsibility because I felt my successful migration has the potential to impact the nature and course of race relations and future opportunities for other blacks’ relationship with Davidson College and the broader issues of integration and opportunities for blacks in higher education and other arenas… I carried with me not only my own hopes and dreams but also those of my family, my community and my people.”

The December 1, 1967 issue of The Davidsonian included an article by Bob Reid entitled “Negroes View Role: ‘Hasn’t Been Exactly Easy’,” which interviewed three of the five black students on campus at the time. This article provides insight into the students’ experience while they were living it:

Leslie Brown ’69: “It hasn’t been exactly easy… You realize just how different you are.”

Calvin Murphy ’70: “When I came here, I wanted to be identified as a Davidson College student. Now I want to be identified as a black Davidson College student.”

Wayne Crumwell ’68: “You can’t integrate fully… here or anywhere else. What good is integrating if the feeling behind it is not real.”

Brown: “You’ll never get a Negro to come here and enjoy it… unless you have a larger Negro student body. Sometimes we like to get away from white students and be with our brothers.”

Brown: “It is generally leading me to dedicate myself to working with black people, and help them realize that there is a pride in being black.”

When interviewed by Davidson student Steven Shames (Class of 1996) for Shames’ honors thesis, “A Good Faith Effort: Integration at Davidson College, 1958-1964,” Wayne Crumwell reflected honestly on his experience as a Davidson student:

“What did I do for Davidson? I graduated from Davidson. I consider that an accomplishment. And I consider that something that was done more for Davidson than for Wayne Crumwell. Davidson needed black students. Black students did not particularly need Davidson… The fact that I don’t feel particularly good about Davidson is something I’ve had to deal with… Would I opt to go to Davidson again? Hell, no! Why subject myself to that trauma during that time in one’s life when you have alternatives?”

Crumwell also discussed with Shames his resentment over how the college administration handled his entrance to Davidson: “It became clear that the college had put some thought into integrating from the perspective of preparing the white students for the experience. But they took for granted the fact that black students would just be accepted in this environment.” He recalled on his return to campus for a talk in February 1993 that the then admissions director “told us we were here for the benefit of white students. They needed to be exposed. It would be an awesome service that we could perform for them.” (The Davidsonian, March 1, 1993)

By 1966, Lefty Driesell (head basketball coach, 1960-1969) has begun to recruit black players for the basketball team. One recruit, Charlie Scott, visited campus with his parents and was taken to the Coffee Cup, a local segregated restaurant. Town legend hold that “the Coffee Cup incident” is the reason that Scott, previously interested in attending Davidson, went on to commit to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill instead: “Many feel the incident influenced Scott’s decision to attend the University of North Carolina and cost the Wildcats a national championship. According to Will Terry, ‘There was an awful lot of desegregation taking place that next afternoon.'” (Davidsonian, May 8, 1981) Leslie Brown also mentioned the Coffee Cup when discussing the town of Davidson’s reaction to black students at the Homecoming 2012 event: “To say you could comfortably sit and enjoy it and either establishment [M&M Soda Shop and Hattie’s] would be an overstatement. Then there was The Coffee Cup which served blacks on a takeout basis only.”

Another one of Lefty Driesell’s recruits who did enroll at Davidson was Mike Maloy (Class of 1970; did not graduate). Maloy remains one of the best basketball players to ever attend Davidson, and holds the distinction of being the first black member of a fraternity at the college. The March 2, 1967 issue of Jet magazine reported: “First Negro Accepted by White Frat In N.C.” when Maloy joined the Sigma Chi fraternity. The story included the total number of students of color in 1967: “The 1,000-member student body has seven Negroes.” Leslie Brown also became a member of Sigma Chi.

In 1967, the Black Student Coalition was founded by these early black students, and remains an active campus organization. The BSC’s Statement of Purpose lists three main objectives:

“to establish and maintain a spirit of solidarity among the Black students of Davidson College,” “to create a sense of awareness within the framework of Davidson College with regards to the contributions of Black students, and specifically the Black Student Coalition, to the ‘total environment’ of Davidson College,” and “to serve as an active force ready and willing to support the Black citizens of the town of Davidson and to aid them in overcoming many of the problems which they now face.”

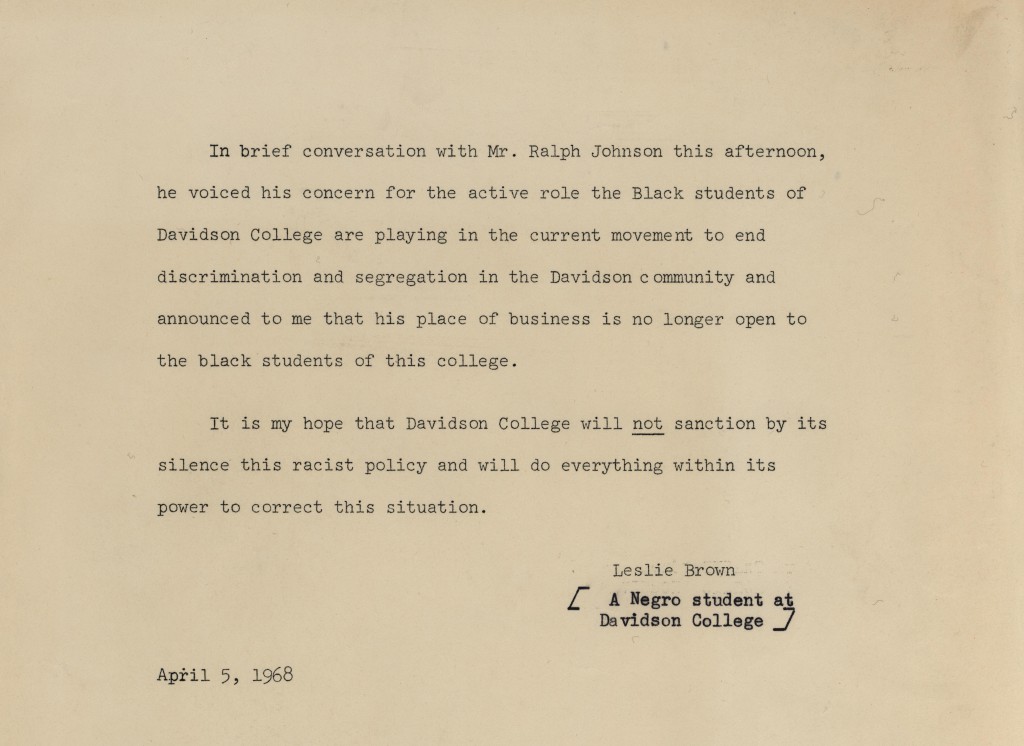

In April 1968, students picketed Johnson’s Barber Shop, a local black-owned segregated business. Johnson’s would serve black Davidson students, but not black townspeople during regular business hours. At the end of the month, a faculty and student committee formed to generate interest in “contributing to a fund to underwrite Mr. Ralph Johnson’s losses if he were to integrate his Barber Shop” reported to President Martin that they had approached Johnson and Hood Norton (who owned another segregated barber shop in town) and “regret to report to you that both Mr. Johnson and Mr. Norton were unreceptive to the entire idea, indicating that their strong intention to adhere to their current policies of segregation.” Dan Rhodes and Wayne Crumwell both served on this committee.

Leslie Brown wrote a letter to President Martin informing him that Johnson had told him he would no longer serve black students in his barbershop, and urged Martin to have the College take an official stance. In an interview for the book One Town, Many Voices: A History of Davidson, North Carolina (Jan Blodgett and Ralph Levering, 2012), Max Polley (faculty in Religion, 1956-1993) recounted a conversation with Ralph Johnson, urging Johnson to integrate:

“When I talked to him, I said, ‘You know, now it’s time. Why don’t you go ahead and cut the hair of the little whites and blacks. It’s coming.’ And he said, ‘Dr. Polley, when I started this shop, the white people said you are only going to cut white people’s hair, and that’s what I did. Now the white people say we want you to cut black people’s hair also. When do I get to make a decision? I just have to do what the white people say.'”

Five weeks after the boycott began, Johnson opened his barbershop to customers of all races during regular business hours. Later that year, Hood Norton’s shop did the same. The barbershop boycott demonstrates that Crumwell and Brown were participating in activism around Davidson during the late 1960s.

By the early 1970s, there were 19 students of color enrolled at Davidson College. Howard J. Ramagli (Class of 1972) surveyed 15 of those students in 1971-1972 for his paper, “A Study of Attitudes & Procedures Related to the Black Experience at Davidson.” In particular, the anonymous comments Ramagli compiled on the topic of black identity in Davidson shed light on the experiences of these early black students:

“I hope I am considered a student at Davidson and not just a black student at Davidson.”

“It’s hard stepping into somebody else’s [the white’s] world, especially when they think their world is right.”

“You have to carry around your ID everywhere to show that you really go to school here. I can’t even get a check cashed or get into the gym without someone asking for my ID to prove who I am.”

“There is a loneliness you have to endure which is beyond any white definition of loneliness.”

“Being black at Davidson is going to homecoming and all the music is blue-grass.”

Davidson College became fully coeducational in the fall of 1973, when the first class of women freshmen enrolled. This first class included four black women: Julia Deck, Denise Fanuiel, Debra Kyle, and Marian Perkins. In 1977, Denise Fanuiel became the first black woman to graduate from Davidson College, as well as the first woman to be commissioned through the college’s ROTC program. Marian Perkins went on to graduate in 1979, and returned to campus to give a talk on her reflections for Black History Month in 1993, along with Wayne Crumwell ’68.

Perkins’ portion of the speech received less coverage in The Davidsonian than Crumwell’s, but did include mention a brief mention of her student experience:

“While outward racism was not so apparent, subtle hints of its presence did not go unnoticed by her. Professors who encouraged her to join their departments so that they might have a black student in their ranks, and a theater production which depicted African Americans in a displeasing light made their points… Perkins used the final moments of her talk to encourage students [to] have deeply committed faith and to promote encouraged race relations. ‘I am deeply committed to my religion and don’t feel the need to judge failure and success using the normal rules.'”

Perkins later became an ordained Baptist minister, and still works with the Greater Fellowship Baptist Church in Decatur, Georgia. Julia Deck and Debra Kyle withdrew from Davidson without graduating.

25 years after Ben Nzengu enrolled at Davidson, he returned to campus for a reunion. A Charlotte Observer article by Pam Kelley, “Challenge of integration remains: Davidson’s first black student attends 25th class reunion” (April 20, 1991) covered the event: “Though aware he was making history, ‘I wasn’t concerned all the time,’ he said. ‘I was concerned with getting my work done.'” Kelley also quoted Anthony Foxx (Class of 1993): “‘I think the main difference between then and now,’ said Anthony Foxx, a black sophomore from Charlotte, ‘is we’ve known because of the people who’ve graduated for the last 20 years, that we can make it through.'”

George Nzongola was interviewed for the Davidson Journal‘s “The Black Experience of Davidson” issue (Fall 1990), on his experiences as a Davidson student, and his thoughts on African-American studies as a professor in the field: “… I think it even more important that Davidson ought to do more to increase the number of African-American students and faculty. I mean this is an American college, and I’m kind of disappointed that after twenty-eight years of integration there are only some sixty black students or so in a student body of fifteen hundred.”

Similarly, Minor Sinclair and Vince Parker’s May 8, 1981 Davidsonian article, “Path of integration is slow and long, continues amid problems” called out the College and community on claiming Davidson has been integrated:

“Twenty years has passed since the College began integration. In hindsight, integration appears as a process, a continuum of slow changes and protracted growing pains. In spite of a few volatile moments, the process ahs [sic] largely been one of gradual compromise within the system in ‘the Davidson way.’ Change has resulted. The College, once an all white institution, now claims one black professor and 45 black students. Yet, is Davidson integrated now? or is the process continuing? or has it been aborted?”

This blog, and the one that precedes it, are intended to shed light on the complex path to integration and the experiences of the first black students at one educational institution. While there is a wealth of material collected by the College Archives & Special Collections, there is also more to know and more to collect, particularly the reflections of the first women of color to attend Davidson. We welcome comments and questions, and seek to continue to learn and share that knowledge with the Davidson community and beyond.